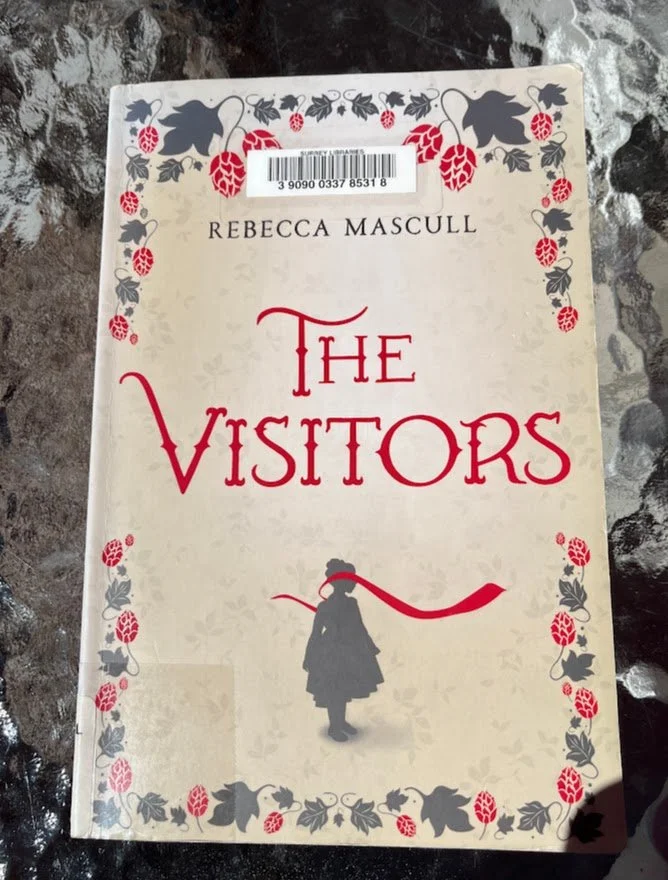

The Visitors by Rebecca Mascull

Born into a well-off family, Liza is nearsighted from birth. At age two she falls ill and loses her hearing along with her remaining sight. This is too much for her mother, who suffered five miscarriages before Liza’s birth. She falls into a depression and takes to her bed, refusing to see her child.

Liza’s father loves her but has little idea of how to help her. When he’s not around, the servants manage her frustrated outbursts by locking her in her room, thus adding to her feelings of isolation. Her companions are the mysterious Visitors that only she she can see.

Liza’s life changes dramatically when by chance she meets Lottie, whose natural sympathy is aroused because she lost a young sister who suffered from the same conditions. On the first day they meet, she begins to teach Liza the finger spelling, which leads to signing, and reading braille. The two are soon fast friends.

Meanwhile, science is marching forward. When she is about fourteen, her father takes her to London to see a doctor who believes he can restore her sight by surgically removing her cataracts lenses and all.

As Liza grows up, she falls in love with Lottie’s brother Caleb, a man whose “sculpted face and calm eyes” belie his restlessness. When the Boer War begins, he jumps at the chance to see the world beyond the oast houses of Kent and the oyster farming of Whitstable. Following a series of unexpected changes at home, Lottie and Liza follow him to South Africa.

This book provides a lens that views the human experience through the eyes of a girl with a double physical disability. Long after her sight is restored, Liza looks back at her younger self, remembering how she used to be: “I sometimes pitied, sometimes hated the deaf-blind child I was.” Like the rest of us, she evolves and matures gradually.

Though Liza can never behave or speak like the sighted and hearing people around her, she alone can see the Visitors. Instinctively certain that others will not believe in this ability, she keeps it hidden, even from her beloved Lottie. Then time and opportunity allow her in a crucial moment to use her special gift to help someone she wants badly to hate.

For me, the timing of reading this couldn’t have been more perfect. Recently, I listened to Rebecca Mascull interview neurologist David Engleman, who spoke of his belief that dreams arise from stimuli blasted into our visual cortex to protect its “real estate” from encroachment by the other senses while we sleep. This makes a lot of sense; it is well known that the brains of blind people turn the visual cortex to honing and intensifying the other senses.

Our senses and perceptions, even consciousness itself, are profound mysteries. In spite of a great deal of study, science has been unable to explain how these things work. Recent research suggests that individuals experience far greater variation in their perceptions than previously thought.

There is so much we don’t know. For many years I have been following he work of Rupert Sheldrake, who has long since broken the taboo held among many scientists of admitting the limits of their theories. As well as his groundbreaking work on morphic resonance, he has carried out a variety of simple experiments that demonstrate how pets know when their owners are coming home and how people know when they’re being stared at from behind. Recently I listened to a podcast about the mysterious ability of homing pigeons to return to base even under the most bizarre constraints.

We are all connected, and I’m not talking about telecommunications and social media. Indeed, I have often thought these inventions are physical demonstrations of the as yet dimly understood ways in which our minds—and yes, I’ll say it our loud—our hearts and souls are connected.

Liza and Lottie are products of the late nineteenth century. In their time, electric lighting and telephones were still quite new. Reel time back before these inventions and imagine how people would have reacted to the news that in a couple of generations it would be possible to touch a button on the wall and light a room, or speak to people thousands of miles away “in real time,” as we say now. Disbelief, certainly. Both Liza and Lottie come across as wise beyond their years and aware beyond their times and culture. Even so, it takes a long time and much trust building before Liza tells Lottie, and later a select few other people about her special ability to see and hear the Visitors.

In research done by Sheldrake years ago, may people admitted to having mysterious knowing beyond the five senses that they kept from others for fear of being labelled mad, just as Liza did. Yet in recent years, it has become more and more permissible to speak about experiences that cannot be explained by ordinary means. This is progress. Mascull’s engrossing story of two nineteenth century women prefigures the lifting of many taboos, including the one about having “strange” abilities, which is arguably still in place, at least to some degree.

We live in interesting and challenging times. I feel most important thing we can do now is to admit the limits of our knowledge and the uncertainty of our rigid certitudes. In this way, both artists like the writer of this wonderful novel and scientists like the ever questing Rupert Sheldrake can help bring new knowledge to light.